The ADS Curation Model

Edwin Henneken (ADS)

20 Mar 2023

Introduction

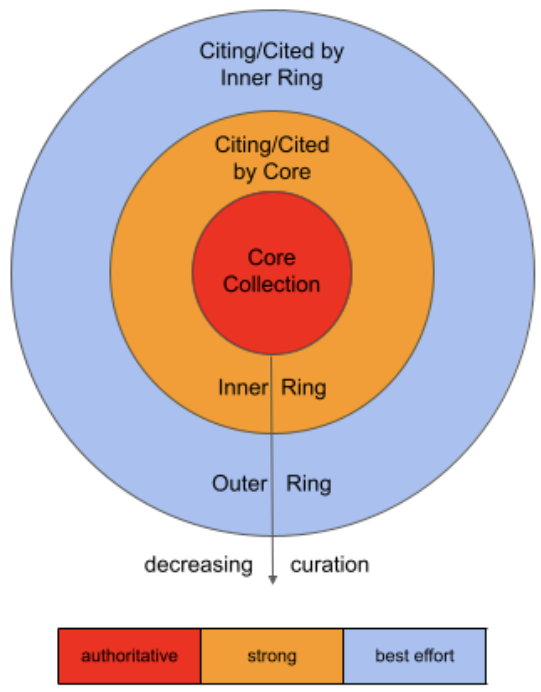

The basic intellectual structure of the ADS can be described using a bullseye model, represented by figure 1. The three rings in this diagram represent different levels of curation applied to the bibliographic content in the ADS. Levels of curation and completeness are different in each ring. The inner region, representing the Core Collection, has the highest level of curation; this segment of the ADS holdings represents that part of scholarly publications where the ADS is considered to be authoritative. In this collection, our users can expect the ADS to be complete, coverage and citation-wise. It is important to keep the following caveat in mind: publications in one ring for one discipline may belong to the other ring in a different discipline. For this reason we implement the following rule: if a journal for any of the disciplines is assigned to the Inner Ring, it should be considered to belong there for all disciplines. In the following sections we consider the following disciplines:

- Astronomy & Astrophysics

- Heliophysics (Solar Physics, Space Weather & Aeronomy)

- Planetary Science

Figure 1: ADS's tiered curation model. The core collection represents disciplines where its curation is strongest and its coverage is authoritative. The surrounding tiers are connected to the core via the citation network.

Most of our curation efforts for the core collection go into maintaining a high level of accuracy, quality and completeness, ranging from the main refereed literature to conference proceedings, theses, gray literature, software, and links to data products. We also nurture all important collaborations necessary for this Core Collection. The Inner Ring consists of publications citing/cited by those in the Core Collection and the Outer Ring consists of publications citing/cited by those in the Inner Ring. These rules are augmented with an additional filter that guarantees that the material added to this ring cites the publications in the Core Collection “with a sufficiently high frequency, in a certain time frame”. Since this is a qualitative statement, we will need heuristics to translate this into a quantitative statement. For example, one contribution to the Inner Ring in Astronomy are those journals being cited by the core astronomy journals, but are not any of the core astronomy journals.

The Core Collection

Historically, the ADS maintained a separate core collections for astronomy, but now that we are expanding our coverage, we are merging the additional disciplines into one definitive Core Collection. For astronomy, we considered the following journals to be the ones that constitute the Core Collection for the Astronomy database:

- The Astrophysical Journal (including Letters and Supplement Series)

- The Astronomical Journal

- Monthly Notices of the R.A.S.

- Astronomy & Astrophysics (including Supplement)

- Annual Reviews of Astronomy & Astrophysics

- Publications of the Astronomical Soviety of the Pacific

- Physical Review D (astronomy content)

The reasoning behind this is mostly qualitative. One of the takeaways in our blog series Citations to Astronomy Journals (parts 1, 2 and 3) is the fact that the publication venues with the most influential research articles are not an immutable set of journals. How can we approach this in a more quantitative way? Any quantitative selection criteria are unavoidably based on journal metrics and just like any metric, journal metrics are not without controversy. We touched on this in our blog Citations to Astronomy Journals 3: Journal Impact. To identify journals to go into our Core Collection, we decided to use the so-called Journal Eigenfactor as the main indicator for journal importance.

The Journal Eigenfactor

Imagine ourselves in a library with actual stacks. This library has an android librarian with an energy source that never needs to be recharged and is completely failsafe, so the android librarian can keep working infinitely long. Being an android, this librarian is equipped with a perfect random generator which will allow it to truly, randomly select a journal volume from the stacks.

Next, from all journal articles cited in this particular journal volume, the librarian randomly selects one.

In the following step, the librarian walks over to the shelf with the journal volume that holds this cited article, takes this volume, and again selects a random citation. Rinse and repeat, ad infinitum. So, what happens when the android librarian draws a citation pointing to a journal that is not in our library? At each time step, with probability α our android librarian proceeds as before. With probability 1-α, it teleports to a node completely at random; it’s in the android’s programming to know how to do this. This way we prevent the possibility of our android librarian getting stuck on a dangling node. In terms of the graph, this means that each so-called dangling node is replaced by one that connects back to the graph using this teleportation mechanism. So, what happens during the journey of the android librarian? The android keeps records, specifically of how often a certain journal is visited. These notes will show, after a while, that most of the time is spent in nodes representing journals that are highly cited by journals that are also highly cited. For each journal, a number is calculated representing how often it is seen. These numbers are stored as a vector in the positronic brain, in which each position corresponds to a specific journal. It turns out that the numbers in this vector start to change much more slowly over time, in fact, they converge to a vector that is stationary. Each entry in this stationary vector corresponds with the so-called Eigenfactor for the journal corresponding to the position in the vector. Without going into the mathematical details, the Eigenfactor of any journal can be interpreted as follows: “the Eigenfactor calculates the percentage of time you would spend at each journal” (West, 2008).

There are some compelling reasons to favor the Eigenfactor. Some of them are the fact that it weights citations with the importance of the citing journals, the fact that it exploits the entire citation network and ignores self-citations and that it has a solid mathematical underpinning and an intuitive stochastic interpretation. Another reason for favoring the Eigenfactor is the fact that it uses a 5-year window to gather citations. This allows, in general, a broader evaluation of journal citations, in particular for disciplines with longer citing half lives.

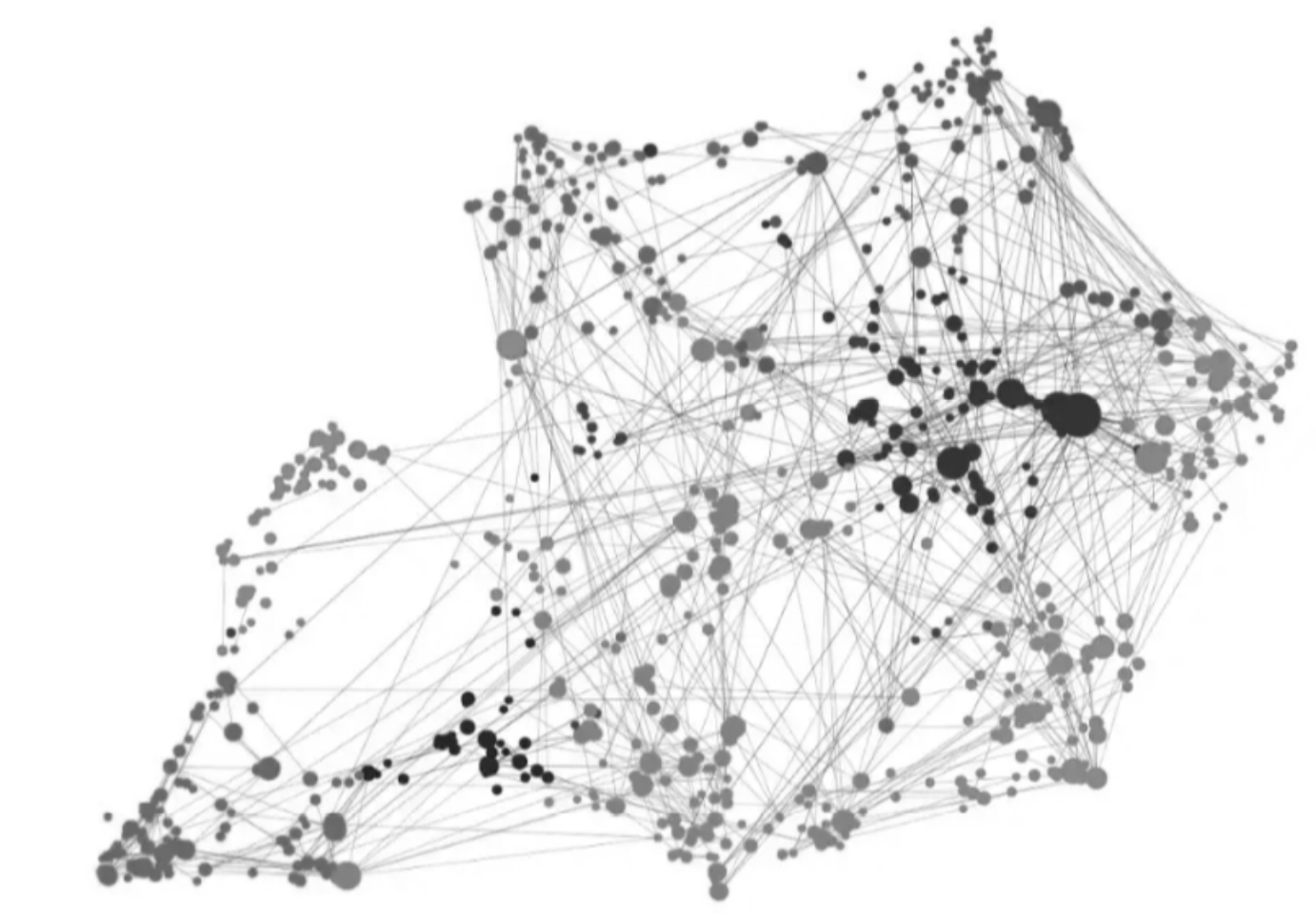

Figure 2: Directed network based on citation relationship between journals. The nodes represent journals. This is a fictitious network, for illustration purposes only.

Figure 2: Directed network based on citation relationship between journals. The nodes represent journals. This is a fictitious network, for illustration purposes only.

At its core, the algorithm that calculates the Eigenfactor values is the well-known PageRank algorithm, which properly deals with the fact that journals are all interconnected in a citation network (see figure 2, showing a fictitious network). The Journal Citation Reports (JCR), published by Clarivate Analytics on the Web of Science platform, provides the Journal Eigenfactor on an annual basis. However, we prefer not to have to depend on an external data source for our decisions. That is why we made a comparison between Journal Eigenfactors calculated using ADS citation data and those listed in the JCR for a number of years.

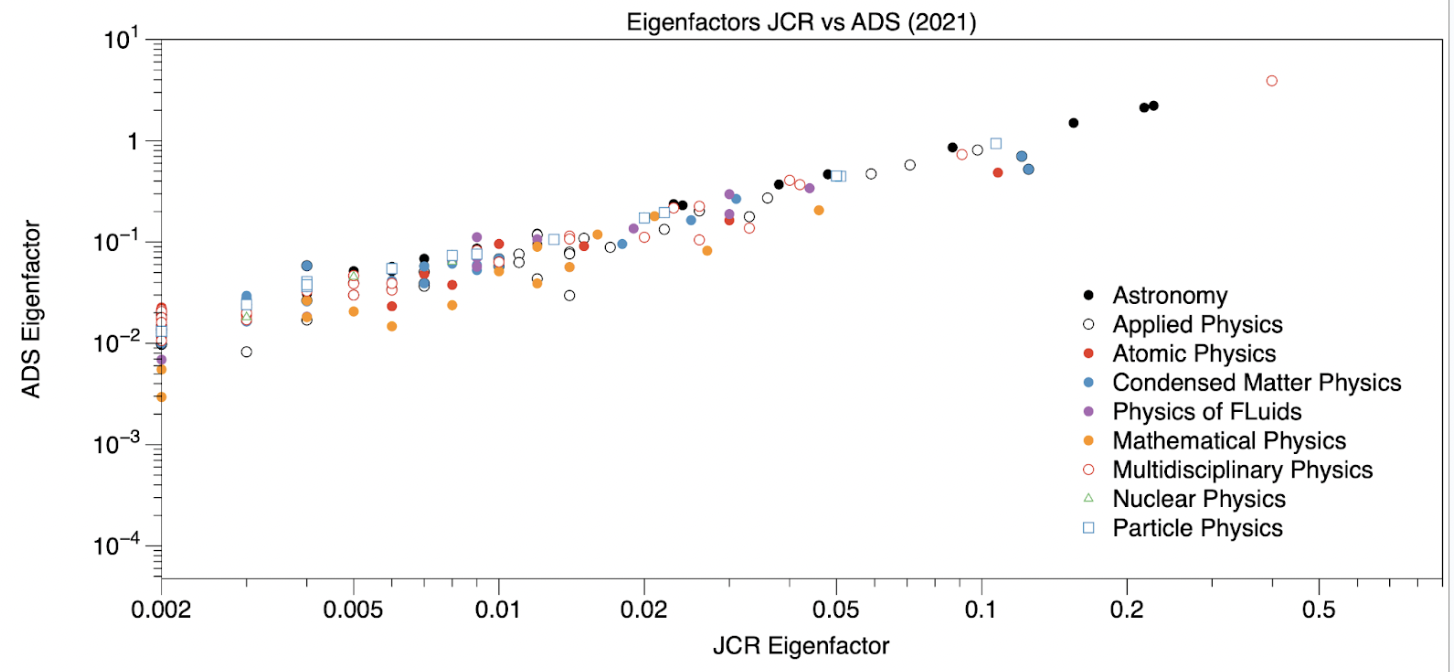

The results are shown in figure 3. The fact that values are not equal is no surprise, because the citation networks in the ADS and Web of Science are different. The encouraging result is that the values have a very strong correlation.

Figure 3: Comparison between Eigenfactors calculated from ADS data and provided in the JCR. The categorization is based on journal assignments provided in the JCR.

Figure 3: Comparison between Eigenfactors calculated from ADS data and provided in the JCR. The categorization is based on journal assignments provided in the JCR.

Next, we compare journal ranking using Eigenfactor values. In other words, if we create a ranked list of journals, how does, say, the top 100 compare with one based on JCR values? In the end, this is what we are looking for. The actual Eigenfactor values are not relevant, since we are only interested in relative values. It is the ranked list that will provide us with the candidates for the Core Collection. We generated and compared the top 100 for the period 2010 thru 2021. For the first decade the top 100 lists are identical; for 2020 and 2021 they only differ in the very tail. For 2020 the ADS list contains the Bulgarian Astronomical Journal (bibstem BlgAJ), where the JCR has Astrophysics (bibstem Ap). For 2021 the ADS list contains Contributions of the Astronomical Observatory Skalnate Pleso (bibstem CoSka), where the JCR has again Astrophysics (bibstem Ap). For both journals, present in the ADS list, Web of Science is highly incomplete.

The ADS Core Collection

For the Core Collection we add the filter that these journals are the top N of the ranked list, such that these journals represent at least 95% of the total sum of Eigenfactor values. This is a meaningful filter, since Eigenfactor values are additive.

The next question is whether it will be sufficient to just accept these lists “as is”? Obviously, these lists need curation. The ADS curation team needs to assess the lists generated. The most likely scenario is that the team feels that a particular journal belongs in the Core Collection, even though the algorithm did not select it. For example, it is possible that a journal with a lot of cross-disciplinary content did not get included. While the ADS citation network is the best one available for core astronomy disciplines, it has known gaps (sometimes significant) for disciplines in the “outskirts” of astronomy and astrophysics (like astrochemistry, astrobiology, astrophotonics, archaeoastronomy and astroinformatics). It is not uncommon for articles in a journal like Astrobiology to have reference lists in the ADS that are only 50% complete. The ADS is also aware that IEEE content is very important for many of its users; by identifying IEEE content as belonging to the Core Collection we can assure completeness will become a top priority. Another possibility is that a journal is too “young” to have acquired a position in the citation network to get a sufficiently large Eigenfactor value; in this case it is purely a qualitative argument to still include it in the Core Collection, assuming that eventually it will position itself as an influential journal within the citation network.

The algorithm, in combination with additional curation work, has resulted in a list of 207 journals.

We will reevaluate this list on a regular basis. We still have to determine what the cadence of this reevaluation will be. The stage of research fields and publication venues is a dynamic one; boundaries between disciplines become less distinct, multimessenger science becomes more prolific and techniques from one discipline turn out to be highly applicable to other ones (like e.g. one developed in astrophysics to cancer research).

astrophysics data system

astrophysics data system