Citations to Astronomy Journals 3: Journal Impact

Edwin Henneken and Michael J. Kurtz (ADS)

26 Mar 2019

This is the third of a series of blog posts measuring the journals that publish astronomy research articles, using citation statistics with a number of different indices. In this post we discuss per article citation rates and how these can be used to create impact factors.

In the previous blog we observed that “market share” does not provide the whole story with regards to journal positioning among other journals. That is why we introduced the concept of “mind share,” to provide a more nuanced picture. Now we will argue that these two indicators still don’t provide the whole story. In the previous 2 installments of our blog we indicated that showing the increase in the interdisciplinary aspect in scholarly publishing is fairly straightforward, whereas making quantitative statements about impact of individual journals is not.

The subject of determining journal impact via indicators is complex (see e.g. Bohannon 2016, Chen 2013, Larivière 2018, Moed 2005, Reedijk 2006). Studies agree that the h-index can be a useful indicator within the right context and if one realizes what its limitations are (Egghe 2012). Egghe concluded that “we are inclined to say that the h-index will become a severe concurrent for the IF [Impact Factor] of a journal.” Nevertheless, the h-index works best in homogeneous environments, e.g. among journals from one discipline. We showed the increasing multidisciplinarity in astronomy, introducing systematic cultural effects, which adds additional layers to the already existing complexity. Because citation distributions are lognormal, measurement uncertainties are multiplicative; this has consequences for citation-based metrics on both author level (Kurtz & Henneken 2017) and the more aggregated journal level.

The Journal Impact Factor (JIF) is, by far, the most discussed bibliometric indicator. The JIF was at first developed to help librarians make subscription decisions, but has now become a proxy for the quality of research and researchers (The San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, DORA, 2013). The JIF has become even more powerful in China, India, and other nations emerging as global research powers. Unfortunately, in some academic environments, publications in journals with a high JIF have a direct impact on funding opportunities. The San Francisco declaration urges all stakeholders to focus on the content of papers, rather than the JIF of the journal in which it was published. DORA’s 18 recommendations call for sweeping changes in scientific assessment. A report from the International Mathematical Union states: “While it is incorrect to say that the impact factor gives no information about individual papers in a journal, the information is surprisingly vague and can be dramatically misleading” (Adler 2009).

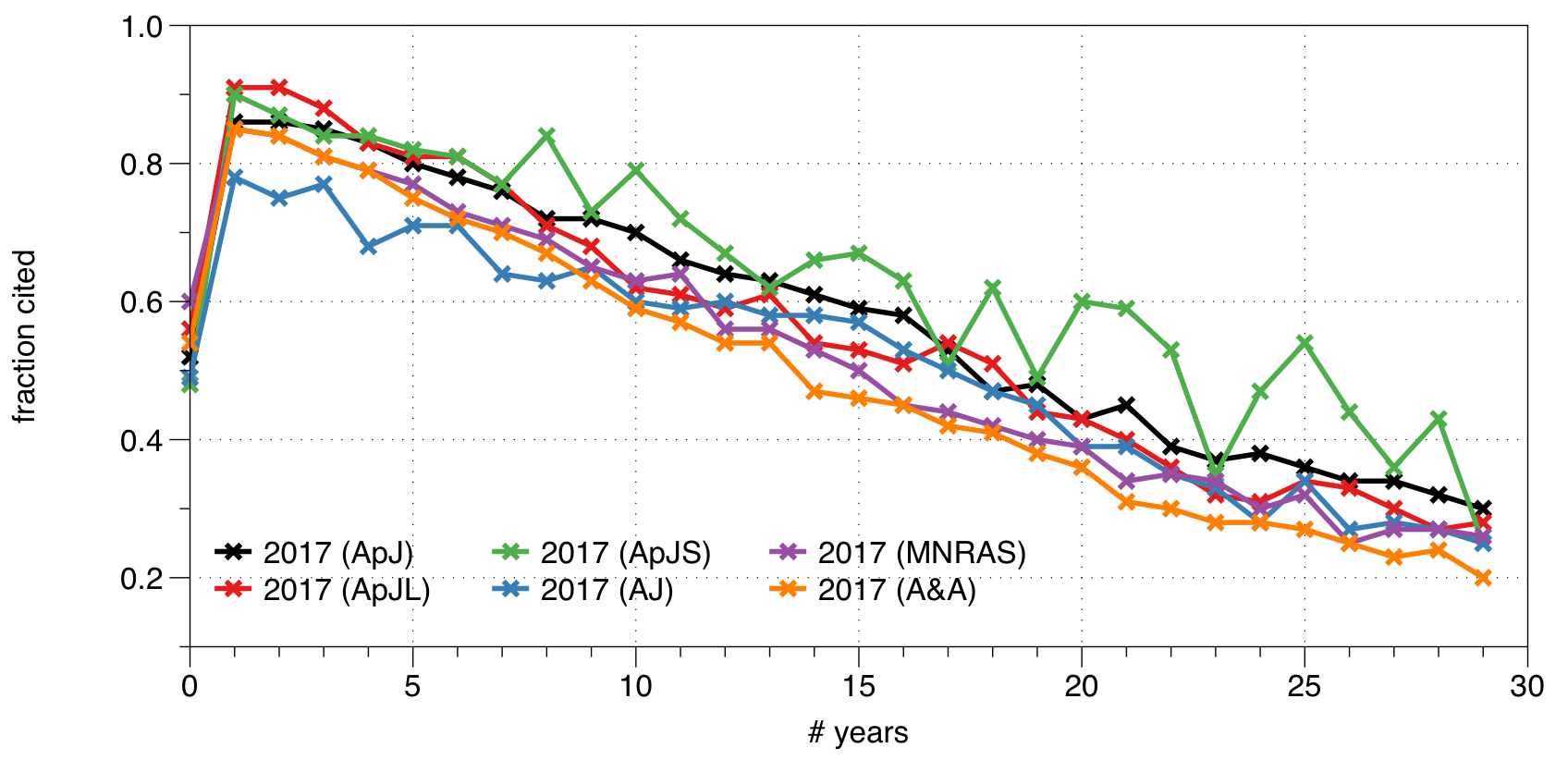

Impact is a form of relative aging. In the case of scholarly articles, aging is often measured by counting citations. As material ages, in general we observe relative decrease in its use, translating into decreasing citation counts. In bibliometrics we refer to this effect as the obsolescence of citations. Qualitatively speaking, the effect is the same across all journals, but there are differences on a quantitative level: relative use differs among journals and in that sense a given journal’s impact is different. Traditional impact measures overlook these longer-term effects. Here we present two different ways to examine these obsolescence effects. First we ask the question: given the references in astronomy articles published in the set of 50 journals in year Y, what fraction of (astronomy content of) journal J is cited in year Y-n? The diagram below present these fractions based on 2017.

Figure 1

Figure 1

The fact that ApJS behaves in a very different way compared to the other journals should not come as a surprise: the publications in this journal are of a very different nature. Publications describing data releases and catalogs are cited in different ways than regular articles. The most interesting features of the diagram below are its short term and long term characteristics. The short term provides a measure for the immediate uptake of research presented in a journal, while the long term can give insight into the extent of how results presented a couple of decades ago are still being used or referred to in current research. The diagram illustrates that the historical component of impact is an important one to take into account when discussing the overall impact of a journal. When you look at just the recent past (of 3 years, for example), the difference between the ApJ, MNRAS and A&A is minimal, but when we look longer-term, the differences become more distinct. The fraction of ApJ articles, published 2 or more decades ago, that is still cited, is consistently higher than that of A&A and MNRAS (significantly higher in the case of A&A).

Next we define an IF, defined as follows:

IF(Y,n) = num total cites to astronomy articles published in year Y in the n years since, divided by number of astronomy articles published in year Y

This IF is another way of quantifying relative aging of citations, or relative use of articles. The diagram below shows a comparison between MNRAS, A&A, and the ApJ (main journal). The dotted line represents equal IF between the ApJ and a given journal. Qualitatively IF ratios grow linearly for the journals in our comparison below (R2=0.9996). However, quantitatively speaking, the MNRAS values of IF are about 0.72 of those for the ApJ for publications from 1997. In the case of A&A articles published in 1997, the IF values are 0.57 of those for the ApJ. In addition to articles published in 1997 (black points), the diagram compares IF values for articles published in 2002 (purple points), 2007 (green points), and 2012 (orange points). For each journal and publication year, a line has been fit to the data, as shown. For 2002 the slope for MNRAS increased to 0.74 and for A&A to 0.61. Again 5 years later, we only see a significant increase for A&A, but the size of the ApJ is still significantly larger. This illustrates the dominance of the ApJ in the field. These shifts in time are due to multiple factors that will be hard to single out. For one, editorial policies change over time. We also know that citation behavior changes over time (see e.g. Henneken et al. 2009, figure 2). We do see the effect we mentioned in the previous blog, of MNRAS catching up with the ApJ. This is illustrated by the data for 2016.

Figure 2

Figure 2

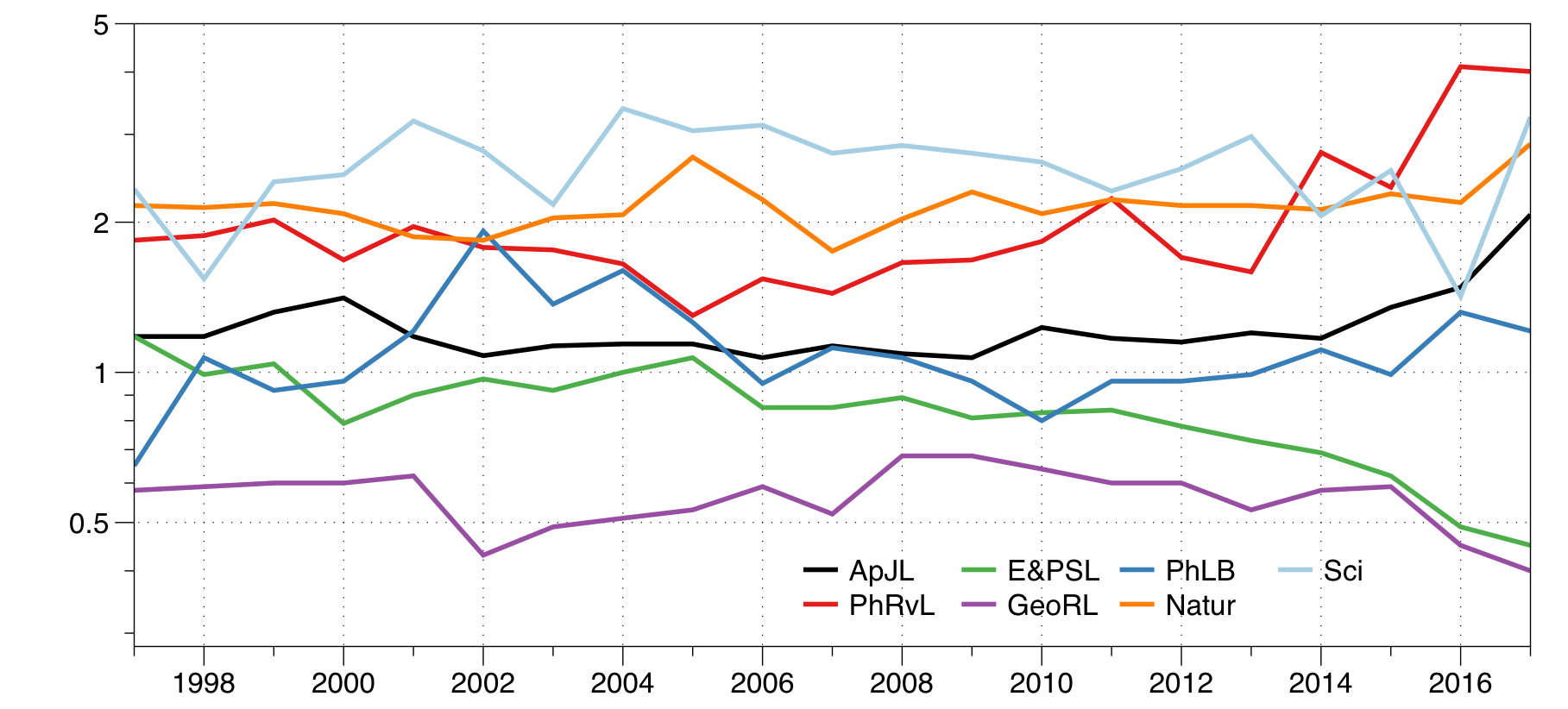

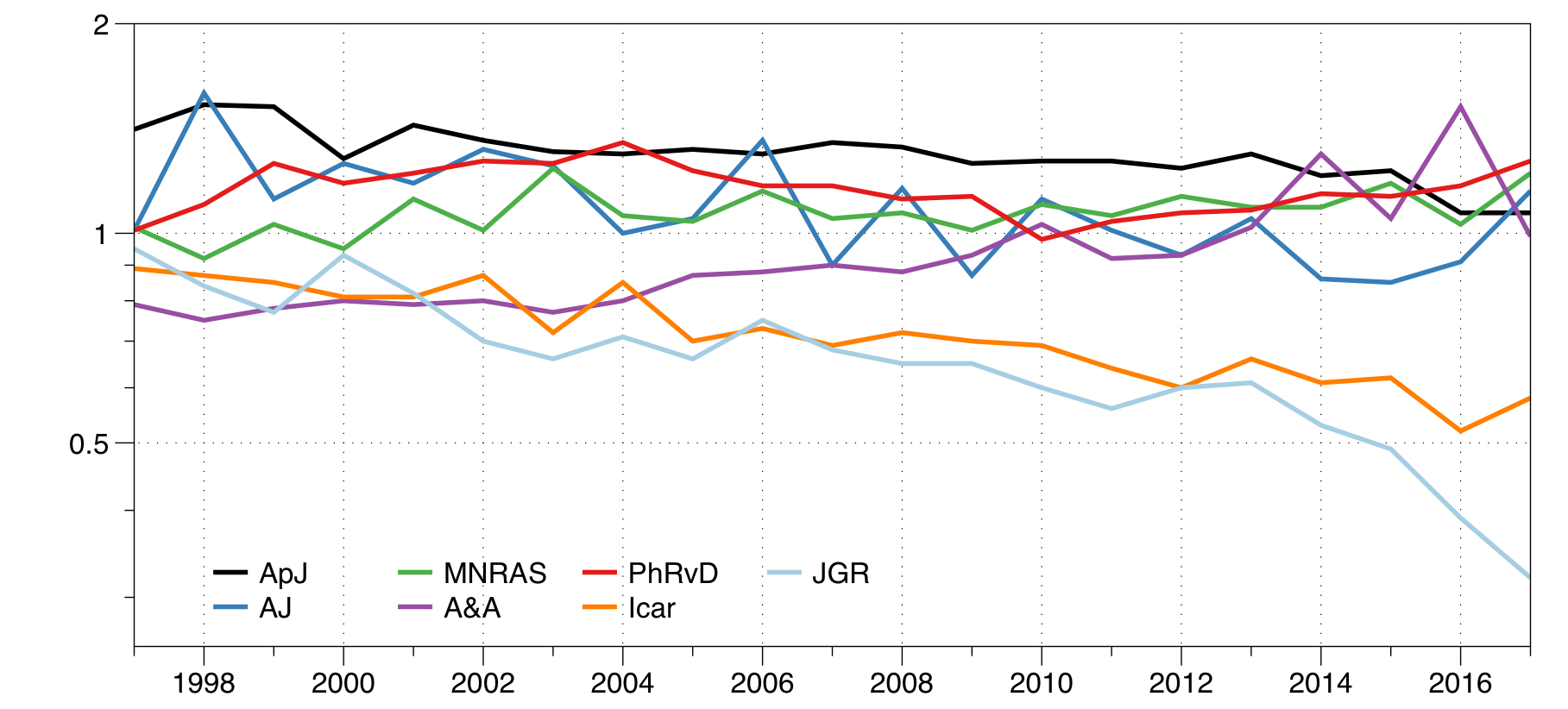

We offer one last way of comparing journals: compare mean cites for astronomy papers relative to mean cites in the Sample Group (consisting of the 50 journals, defined in the first blog). Here we may look at “Letter journals” and “Regular journals” separately, because these are different classes in terms of citation rates.

Figure 3

Figure 3

The relatively steep rise for PhRvL is largely due to gravitational wave publications, especially the LIGO papers, just like how the Planck papers skew the results for A&A (see diagram below). Values for 2017, and probably even 2016, should be interpreted with some caution, because these publications are still actively accumulating significant citations. It is also worth noting that a journal like E&PSL is very much embedded in the Earth Sciences discipline, which has very different citation rates.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Besides the caveats of a more philosophical nature we mentioned earlier, the main takeaway is that by restricting the determination of a journal impact factor to just 2 years is doing most journals injustice. A journal like the ApJ is a dominant source of information for the discipline, precisely because its contents stay relevant for so long, as indicated by our data for the fraction of articles being cited.

In our blog series we have explored the landscape of astronomy-related refereed scholarly literature. It is important to emphasize this fact, because this selection criterion is less restrictive than using publications defined as astro/planetary. For example, many Earth Sciences papers are related to Planetary Science, but are not strictly Planetary Science papers. We are grateful to Keith Smith for having pointed out that it is crucial to highlight this selection criterion. Our analysis clearly shows the interdisciplinary nature of current astronomy research and also the shifts in publications venues. These shifts have expressed themselves in the levelling of the playing field of journals. This levelling followed from the results shown in the second blog, but it also follows from the perspective offered in this blog.

astrophysics data system

astrophysics data system